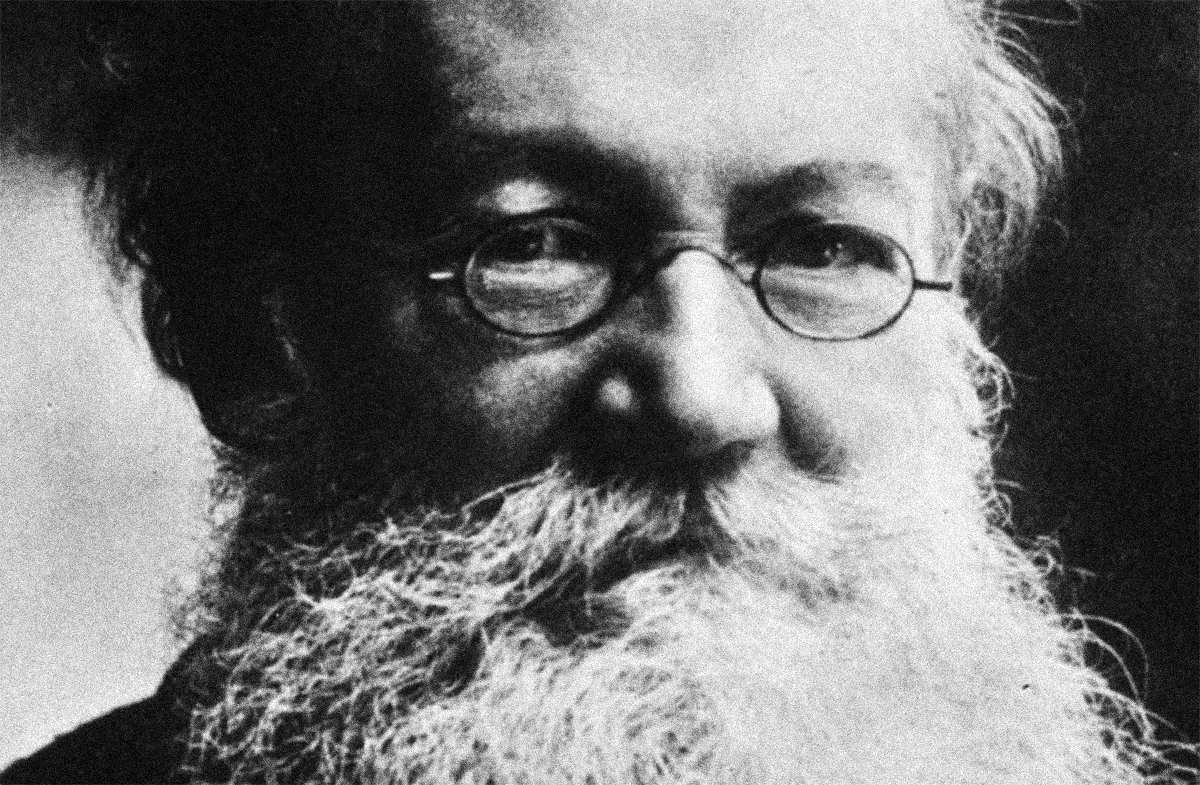

Anarchist Morality — Peter Kropotkin

Peter Kropotkin was a Russian prince and a prominent Russian anarchist. Throughout his life, he advocated for a communalist society free from central government. He wrote many books, essays, and articles on the subject of anarchist communism and was known throughout Russia as “the Anarchist Prince.” The following is an excerpt from his 1897 essay, “Anarchist Morality.”

We have seen that men's actions (their deliberate and conscious actions, for we will speak afterwards of unconscioushabits) all have the same origin. Those that are called virtuous and those that are designated as vicious, great devotions and petty knaveries, acts that attract and acts that repel, all spring from a common source. All are performed in answer to some need of the individual's nature, all have for their end the quest of pleasure, the desire to avoid pain.

We have seen this in the last section, which is but a very succinct summary of a mass of facts that might be brought forward in support of this view. It is easy to understand how this explanation makes those still imbued with religious principles cry out. It leaves no room for the supernatural. It throws over the idea of an immortal soul. If man only acts in obedience to the needs of his nature, if he is, so to say, but a "conscious automaton," what becomes of the immortal soul? What of immortality, that last refuge of those who have known too few pleasures and too many sufferings, and who dream of finding some compensation in another world?

It is easy to understand how people who have grown upin prejudice and with but little confidence in science, whichhas so often deceived them, people who are led by feelingrather than thought, reject an explanation which takes from them their last hope.

Mosaic, Buddhist, Christian and Mussulman theologians have had recourse to divine inspiration to distinguish between good and evil. They have seen that man, be he savage or civilised, ignorant or learned, perverse or kindly and honest, always knows if he is acting well or ill, especially always knows if he is acting ill. And as they have found no explanation of this general fact, they have put it down to divine inspiration. Metaphysical philosophers, on their side, have told us of conscience, of a mystic “imperative,” and, after all, have changed nothing but the phrases.

But neither have known how to estimate the very simple and very striking fact that animals living in societies are also able to distinguish between good and evil, just as man does. Moreover, their conceptions of good and evil are of the same nature as those of man. Among the best developed representatives of each separate class, — fish, insects, birds, mammals,—they are even identical.

The ant, the bird, the marmot, the savage have read neither Kant nor the fathers of the Church nor even Moses. And yet all have the same idea of good and evil. And if you reflect for a moment on what lies at the bottom of this idea, you will see directly that what is considered as good among ants, marmots, and Christian or atheist moralists is that which is useful for the preservation of the race; and that which is considered evil is that which is hurtful for race preservation. Not for the individual, as Bentham and Mill put it, but fair and good for the whole race.

The idea of good and evil has thus nothing to do with religion or a mystic conscience. It is a natural need of animal races. And when founders of religions, philosophers, and moralists tell us of divine or metaphysical entities, they are only recasting what each ant, each sparrow practises in its little society.

Is this useful to society? Then it is good. Is this hurtful? Then it is bad.

This idea may be extremely restricted among inferior animals, it may be enlarged among the more advanced animals; but its essence always remains the same. . . .

The idea of good and evil exists within humanity itself. Man, whatever degree of intellectual development he may have attained, however his ideas may be obscured by prejudices and personal interest in general, considers as good that which is useful to the society wherein he lives, and as evil that which is hurtful to it.