Black Power vs White Power

An examination of the history, foundations, inspirations, and aims of these two controversial movements vying for racial power.

Power. Everybody wants it, everybody needs it – individuals, organizations, nations. It’s man’s Achilles heel, yet, all at once, his sustenance. Just five simple letters, but a big word, containing oh-so-much.

According to the Oxford Dictionary, the most basic definition of "power" is "the ability to do or act." When one thinks of White Power, one could be forgiven for focusing on the mainstream powers that be. The world is dominated by the West. The influential forces therein are composed of white Americans and Europeans. Whatever anyone thinks, their ability ‘to do and act’ is unquestionable. Albeit condemned at worst, their power is respected, the world over.

There somehow exists, however, a more particular, peculiar White Power: the power that arose because it felt the existence of its national values was being threatened. Until the power of a minority race seemed a possibility, there was no real need to talk about White Power. So in terms of the human experience, it’s a relatively recent phenomenon. You see, White Power had been a fact for a very long time. It was self-evident. They ruled the waves and the land. They were the ones who enslaved other peoples. They led The Renaissance. They sparked and fuelled the Industrial Revolution. They were viewed as the masters of civilization. Their numerous conquests, colonial gains, and the institution of slavery had put other peoples in their place, psychologically and materially.

An appeal to the American Congress in 1868 reflected the self-assuredness of White Power: ‘The white people of our state will never quietly submit to Negro rule… We will keep up this contest until we have regained the heritage of political control handed down to us by honored ancestry. That is a duty we owe to the land that is ours, to the graves that it contains, and to the race of which you and we alike are members – the proud Caucasian race, whose sovereignty on earth God has ordained.’

During the years that followed The American Civil war, the new Republican government attempted to effect the politicization of blacks in order to hasten the development of industrialization, an inherent threat to the survival of the southern slave-based economy in America. The need to reassert white authority became real. This led to the rise of pro-white organizations. They sought to undermine and intimidate white southerners who shared Republican ideals, and terrorize blacks who showed pretensions about enjoying newly gained freedoms. The most renowned of these organizations was the Ku Klux Klan.

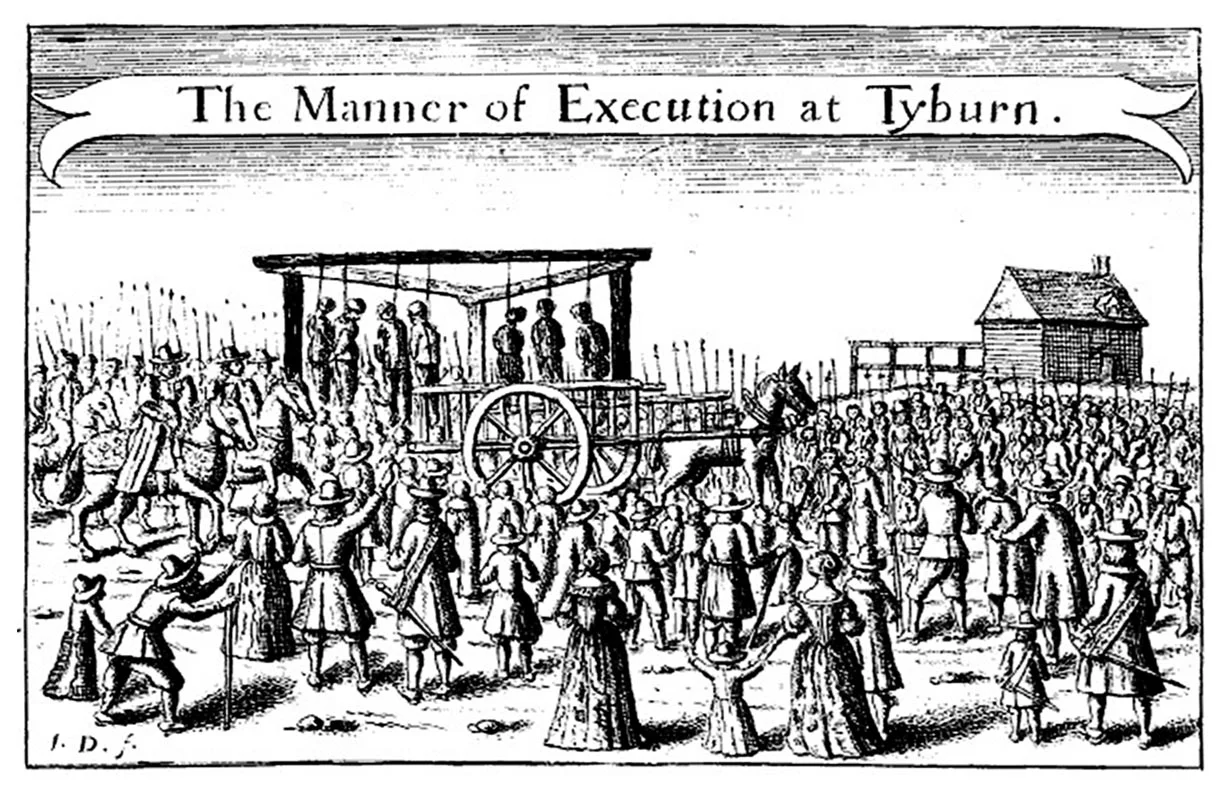

Its beginnings date back to 1866, in Pulaski, Tennessee. Said to have started as a mere social club to bring respite from hardships that came with the Reconstruction years, it quickly became one of the most brutal organizations that has, to date, marred American history. Lynchings, drownings and mindless arson attacks on black homes, and their other buildings, characterized their protest.

Though these horrific images were well known, it wasn’t until the 1950s that British whites began to articulate their own needs for some form of White Power. The vision of 50s Tory MP, Enoch Powell, very much provided the impetus for organizations soon to be formed. Mass immigration, particularly from the West Indies, began to create a sense that white values were being undermined. In 1967, under the leadership of one Authur K. Chesterton, the National Front came into being. It was an amalgamation of the Racial Preservation Society, the British National Party, and the League of Empire Loyalists. Tired of disunity among whites, they came together in agreement that, 'British people have a right to determine their own future; that multiculturalism and mass immigration was a tragic mistake; that patriotism is laudable…’

By the early 1970s, Asians began to join the throng of blacks coming from overseas. As organizations such as the NF fuelled fears of the anxious British public, their numbers grew. Their popularity began to be reflected in local election results. In 1973, Martin Webster, parliamentary candidate for West Bromwich in the West Midlands, gained nearly 5000 votes, 16% of the poll. Media coverage of racist incidents, in which they were involved, seemed to advance their cause. When, in 1976, Robert Relf, a vendor who installed a sign stating that his house was for sale only to English buyers, the NF campaigned in his support. Their votes soared.

The NF had evolved into a political party. Despite attempts to diversify its campaign base, to include objections to the Common Market and a voice for Ulster Loyalists, immigration, and the call to keep Britain white were always chief ideals. By the 1979 General Election, hopes of gaining seats in parliament seemed realistic, and over 300 candidates were proposed. Mainstream parties had to see them as a force to be reckoned with! Thus, in 1979, Margaret Thatcher, prime minister in waiting, made a speech in which she declared that she, ‘understood the fears of British people being swamped by coloured immigrants.’ This proved to be the sympathetic ear longed for. Thatcher’s move, bad press and campaigns against them by anti-Nazi factions, dictated disappointing results in the election. The Conservatives’ version of White Power proved sufficient for masses ready to give their vote to the National Front.

By the 1980s, NF members began to realize that a change was needed. The party began to fragment. One of it members, John Tyndall, formed the BNP in 1982. By the 90s, it began to achieve successes in by-elections. In 1993, the BNP secured a seat in East London’s borough of Tower Hamlets. Characterized by violence reminiscent of their forerunners, the Ku Klux Klan, it formed Combat 18 as its security wing. This was used to protect BNP meetings, and leaders during marches. They also carried out racist attacks and murders.

Today, its leader is Nick Griffin. His argument is that ‘we must preserve the white race because it has been responsible for all the good things in civilization.’ Despite this statement seeming anachronistic in many ways, it certainly hasn’t lost its appeal. Its intentions to outlaw mixed race relationships and throw black criminals out of Britain, even if they were born here, still appeals. In 2002, the BNP won 3 council seats in Burnley. In Oldham, it came second in four of their five wards. Immigration and asylum seekers are still proving key and poignant issues today.

The beginnings of Black Power as a force to be reckoned with in America really began after the Reconstruction in the 1860s. Dreams of equality slowly began to seem an achievable end, and efforts to bring this about started to take shape. By 1909, the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People was formed under its first name, the National Negro Committee. By the 1920s, blacks began to leave southern states in droves, heading for northern cities in search of jobs. Attitudes began to change. The racial consciousness of blacks strengthened, as did their level of assertiveness. This was helped along by the Harlem Renaissance, when black achievements in the Arts began to flourish. Marcus Garvey, the leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, was the primary voice of African Nationalism. He struck the flame that later fired into the movement for black rights. And the NAACP stepped up their lobbying of the national government for improvements for black people.

Despite the American creed of independence, freedom and equality of all men, it wasn’t until the 1960s that blacks began to feel the real impact and significance of any changes. Martin Luther King led the Civil Rights Movement. His non-violent approach brought about changes which led to the breakdown of many segregationist principles. But not all blacks were completely satisfied with his style of protest. The Nation of Islam, its most prominent spokesperson being Malcolm X, felt that white people should be confronted head-on, with force. His message rang true to many ghetto blacks living in poverty and suffering daily discrimination in America’s cities: "I don’t go along with non-violence unless everybody’s going to be non-violent. If they make the Ku Klux Klan non-violent, I’ll be non-violent." The wrath of Black Power had begun to be felt.

Malcolm X’s assassination in 1965 seemed to create a feeling that his legacy of direct rhetoric and the fearlessness of attitude should not die with him, and in 1966, the Black Power movement was born. The term is said to have been first used by Robert Williams, a long-time activist for black civil rights. He and Black Panther leader, Stokely Carmichael, were chief players in formulating the precepts of the movement.

Despite agreement that black people were to be treated with dignity - politically, economically and socially - Black Power meant different things to different people. The Black Panther Party was one of the chief exponents of Black Power. This militant group believed strongly in defending themselves against racist America. Their determination led them to openly arm themselves and defy injustice wherever and whenever it appeared. Stokely Carmichael’s words typified the rhetoric of the Panthers: ‘I’m not going to beg the white man for anything I deserve – I’m going to take it. We want Black Power.’

The movement also had a very significant psychological impact on black people. Another of its strands focused on asserting black pride. ‘Black is beautiful,’ one of its slogans, promoted a rejection of efforts to adopt European hairstyles and appearance. Natural African hair, in the form of neatly shaped afros and lines of canerow, were brandished; African dashikis and head wraps were worn; dark skins and flat noses were praised.

There were also those who were completely against integration with whites. They wanted a black society from which whites were barred. They wanted economic and political sovereignty. More liberal others were prepared to accept the Black Power philosophy only until the playing field for blacks leveled. At this time, they would be able to participate in society on an equal footing and the radicalism inherent in the call for Black Power would then become redundant.

This movement began in America, but its impact extended beyond. In Britain, a Trinidadian called Michael DeFreitas took the lead. He renamed himself Michael X. When the Black Power movement had taken hold in America, Michael X was active as president of RAAS, the Racial Adjustment Action Society. Though more conciliatory than the most radical dimensions of the movement, this organization still sought to assert the determination of blacks to confront injustices and discontentment in a way that represented the self-reliance and fearlessness characteristic of Black Power.

In August 1970, the arrest of a black man led to protesters laying siege to Caledonian Road Police Station. Speaking to a reporter for the Sunday Telegraph, Michael X, leader of the protest said:

"If we decide to enter a police station to take someone out there is no way of stopping it…It’s obvious someone is going to be hurt. We’re not eager to place ourselves on a war footing. As warriors it’s obvious if you want to pull down a town at any time we can do it. All one needs is petrol and matches. But we would rather find ways of working to establish harmony between peoples."

It wasn’t long after that Rastafarianism in Britain was also on the brink of finding a strong footing amongst Britain’s black youth. They too felt a sense of kinship with the movement and shouts for Black Power were strengthened. Against a background of routine inequality, discrimination in schools, work places and on the streets, Black Power was greeted with relief and zeal. Black people had found their voice and were not just going to be heard: they were going to be listened to!

Except perhaps dispersed on the fringes, there is no virulence in any talk of Black Power nowadays. Despite this, a deep-rooted dissatisfaction with the socio-political status quo can still be sensed.

Trevor Phillips, the current Chair for the Commission for Racial Equality, boldly voices this discontent:

"Imagine new federations of schools where those who have become ghettoized through their catchment areas are able to join together with others to drive and lift standards… Ironically the real potential of this White Power could be to deliver true Black Power."

He merely flirts with the expression to express a need for the radicalization of school reforms; that seems to be as forceful as it gets now.

Power: "the ability to do or act."

This is true whether the power is white or black. There is a feeling that some whites resent not being able to have pride in their race in the same way that other nations do, and some reaction to this is inevitable. But despite gains made by White Power advocates, such as the BNP, the general consensus is that their inherent racism is not respected in mainstream political arenas. This can only be considered a saving grace. And the issue of resentment is neither here nor there. As we endeavour to make our judgment about the legitimacy of power and pride, one has to ask whether the power can be seen as just or justified.

When drawing comparisons between White Power and Black Power, one may do well to question whether it is offensive or defensive, ultimately pursuing equity or simply some profanity.